For a lot of people, being a top-tier bank executive would be good enough — and a good reason to turn in early once the workday ended. But not for Ramiro Ortiz, who eventually rose to the role of president at SunTrust Bank and BankUnited — all the while moonlighting as a boxing promoter.

“Even while I was working in banking, I promoted boxing shows at War Memorial in the early ’80s,” says Ortiz, who later promoted fights at Magic City Casino. “That makes for an interesting whirlwind, when you’re a banker by day and a boxing promoter by night.”

Ortiz got hooked on the sweet science at a young age. Despite mounting a 7-0 record as an amateur, he determined that he’d be better off banking than boxing.

“In sports, there’s what appears to be little difference from one level to the next,” he says. “But when you’re competing, you understand that level is almost like a mountain you have to climb.”

He always kept one foot in the ring, however, including frequent visits to the original — and legendary — Fifth Street Gym in Miami Beach.

“The first floor was a drugstore,” he says of the second-floor gym, which boasted Angelo Dundee as its trainer. “You walked up this rickety, old wooden staircase. All these great fighters in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, and early ’80s, they worked out there — Roberto Durán, Sugar Ray Leonard, Sugar Ray Robinson. I still remember the first day I walked in there, the number-one lightweight in the world, Douglas Vaillant, runs past me.”

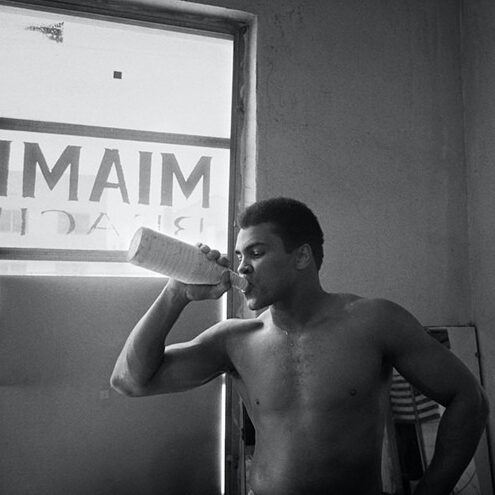

But of all the greats who trained at the gym, none was as magnetic or majestic as Muhammad Ali. The famed fighter, who died in 2016, is the subject of a photography exhibit at HistoryMiami Museum, where Ortiz formerly served as CEO.

Created and curated by Miami-based photographer Andrew Kaufman, “ALI/MIA” consists of silver gelatin prints of Ali from negatives in the Louisville Journal-Courier‘s archives. Most of the photos depict the famed boxer training and going about his daily life in Miami during the runup to his first fight against Joe Frazier — a championship match that took place 50 years ago this month, one that is remembered in the annals of boxing as “The Fight of the Century.”

(Ali and Frazier were undefeated prior to the 15-round bout, which was contested on March 8, 1971, at Madison Square Garden in New York. Frazier won in a unanimous decision, though both fighters emerged from the fight battered and bloodied. Ali would go on win two subsequent — and equally hard-fought — rematches, in 1974 and 1975.)

The exhibit, which runs through August 29, is displayed in a new gallery space that will showcase South Florida photography through HistoryMiami’s collection of more than two million images.

In one of those images, shot by Larry Spitzer, Ali adjusts his shirt outside Wolfie’s, the iconic, 24-hour delicatessen that stood for 60 years at 21st Street and Collins Avenue.

When you think of Muhammad Ali, “Jewish deli” probably isn’t the first term that comes to mind. But to know Miami Beach in the early ’70s is to understand the connection.

“By that time, there were a lot of Jews in Miami Beach,” notes local historian Marvin Dunn, a professor emeritus at Florida International University. “It was the end of segregation and the beginning of integrated society. It was a dramatic moment in terms of civil rights coming to the fore as the new reality. Ali may have been the first Black person who was identified with Miami Beach, unless you were a maid or gardener.

“He was also still a Black man in Miami, and there were still dangers with that,” adds Dunn, who himself is Black. “He could have gotten killed running across the Causeway in the dark. He suffered the same demeaning insults that any Black person in Miami did at the time. It hurt him; it hurt all of us.”

Specific to Wolfie’s, Dunn says, “I used to go there for breakfast. It was one of the few places on the beach where a Black person could go and not feel uncomfortable, partially because there were so many northerners in there. It was also a political hotbed. Politicians met there; decisions were made there. It was kind of a focal point, both in terms of celebrity and one of the first places that was accepting of African-Americans. I got introduced to sauerkraut there. Corned-beef sandwiches, pastrami — I hadn’t had any of that stuff before.”

Recalls Ramiro Ortiz, paraphrasing Ali’s cornerman, Ferdie Pacheco: “Cassius Clay was born in Louisville, but Muhammad Ali was made in Miami.”

Then known by his birth name, Ali first appeared in the city shortly after winning gold at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Over the years, he lived in many of Miami’s neighborhoods, including Overtown, the cultural cradle of Black Miami.

As Dunn sees it, the boxer’s presence over the years bestowed upon Black Miami “a heightened sense of importance.”

Many of the photographs that comprise “ALI/MIA” depict Ali training, relaxing, or interacting with onlookers at the Fifth Street Gym, where he was “bathed in this gorgeous Miami light,” says curator Andrew Kaufman.

Kaufman stumbled onto the project in 2018 after a friend pored through the Ali archives in the Courier-Journal‘s photo department. The newspaper had been photographing Ali’s exploits since the Louisville native was a 12-year-old amateur and had in its possession a multitude of compelling images that had never seen the light of day.

Kaufman’s friend mentioned in passing that some of these photos were of Ali in Miami, so Kaufman asked to see them. About six months later, he got his hands on the negatives. He culled his favorites, hit the darkroom, and came out with the portfolio that would become “ALI/MIA.”

Not long afterward, the Colony Theatre on Lincoln Road staged a play called One Night in Miami, which imagines a night of spirited conversation between Ali, Malcolm X, the singer Sam Cooke and the football star Jim Brown in a Hampton House hotel room after Ali won the heavyweight title from Sonny Liston at the Miami Beach Convention Center in February of 1964. The Colony displayed the photos in its lobby for the duration of the play’s run.

After the play ended, the set — and Kaufman’s prints — headed to the Hampton House as an installment. Kaufman then added eight famous Ali photographs to his Colony collection for a larger installment at the Betsy Hotel, where someone at the Knight Foundation saw them. The foundation arranged for a grant to enable HistoryMiami to purchase the prints. (As for One Night in Miami, last year saw the release of a film version of the play, which recently garnered three Oscar nominations, including one for Best Adapted Screenplay.) The Courier-Journal also compiled a book, Picture: Muhammad Ali — A Rare Glimpse Into the Life of the Champ, which contains hundreds of photos from the archive that span Ali’s life from the time he won his first Golden Gloves championship at age 12.

“Ali’s mark on Miami is absolute,” says Kaufman. “When I got to be in the darkroom and hold the negatives of Muhammad Ali at Wolfie’s or the Fifth Street Gym or on Collins Avenue leaning over a Miami Herald newspaper box, the nostalgia was intense. These were all the places I’d seen as a child visiting my grandparents on Miami Beach. I’m from New York City, and to see the Miami Beach of my childhood was an experience I’ll never forget. Collaborating with Muhammad Ali in a sense is one of the highlights of my career.”

Jebb Harris wasn’t in Miami when Ali was training for the Fight of the Century, but the former Courier-Journal photographer was in the Bahamas when the champ fought the final bout of his career, against Trevor Berbick in 1981. Showing the early signs of Parkinson’s, Ali lost a ten-round decision, and three of Harris’ photos from that final trip are included in the “ALI/MIA” exhibit.

Harris recalls that he was with a colleague when one of Ali’s handlers told them to “be at the fountain at 6 a.m.” the day of the fight. They showed up on foot, and at the fountain they found, in Harris’ words, “a limo following Ali, who was jogging and shadowboxing. The sun was coming up over the ocean and it was just beautiful. We get about a mile out in the country and the limo stops and Ali gets into it. We thought it would be a long walk back, but Ali sticks his head out and says, ‘Come on, get in,’ and drove us back to his condo.”

Of the champ’s hallmark wit, Harris adds, “He’d say, ‘I should be on a postage stamp because that’s the only way I’m gonna get licked.’ He made great copy; he was so quick. Later on, he was frail and had someone guiding him through the crowd. Years later, when I too got Parkinson’s, it occurred to me how hard that must have been for him to be so fast and so agile and then have to have somebody have to walk you through a crowd.”